Introduction: The Hidden Disaster Lurking in Your US Portfolio

Imagine a scenario that has become all too real for international investors: You are a successful entrepreneur living in Switzerland with a modest but meaningful US stock portfolio worth USD 500,000. You hold blue-chip names like Apple and Microsoft, diversifying your wealth across the world’s most dynamic market. Your Swiss bank manages everything professionally and securely. You sleep peacefully, confident that this carefully built legacy will pass smoothly to your heirs.

Then you die.

Within weeks, your heirs contact the Swiss bank to settle your affairs. They are told the account is frozen. The reason: the bank cannot release your US securities without clearance from an entity no one expected—the United States Internal Revenue Service (IRS). What follows is a shock: the IRS claims approximately USD 120,000 of your USD 500,000 portfolio as estate tax.

Your heirs now face an 18-month nightmare of frozen assets, IRS forms, and legal fees. The inheritance that should have been straightforward becomes an international tax crisis.

This is not a worst-case scenario. This is the reality for thousands of foreign nationals holding US investments in Swiss bank accounts. And in 2026, the situation is about to become much worse.

Why 2026 Changes Everything: The TCJA Sunset and Increased IRS Scrutiny

Before diving into strategies, you need to understand the timing issue that makes this urgent in 2026.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 temporarily increased the federal estate tax exemption to approximately USD 13.99 million for US citizens (as of 2025). This exemption is set to expire—or “sunset”—at the end of 2025. When it expires, the exemption will revert to approximately USD 7 million (adjusted for inflation), effectively cutting the shield in half.

Why This Matters to Non-Resident Aliens (NRAs)

While the NRA exemption remains fixed at the paltry USD 60,000, the sunset creates a new compliance environment. Here is why:

Revenue Pressure: The federal government will face a significant revenue shortfall as the exemption shrinks for US citizens. This creates pressure to maximize revenue collection from all sources, including foreign estates.

Increased Scrutiny: With fewer US citizens and residents avoiding estate tax entirely, the IRS is expected to increase its focus on non-resident estates—a lower-hanging fruit with higher-value targets.

Heightened Documentation Requirements: Banks and tax authorities will likely implement stricter verification of worldwide assets and situs assets. The “wait and see” approach is no longer viable.

The Pro-rata Calculation Risk: For those using treaty benefits (more on this below), changes in IRS guidance could alter how the pro-rata exemption is calculated, potentially narrowing benefits.

Bottom line: Acting now, before this compliance environment hardens further, is critical. Delays increase risk.

The Harsh Reality: USD 60,000 vs. USD 13.99 Million

The United States operates a two-tiered estate tax system, and where you are classified determines everything.

For US Citizens and Residents: The USD 13.99 Million Shield

US citizens and domiciliaries receive a generous exemption. In 2025, a US person can transfer approximately USD 13.99 million in worldwide assets—including stocks held anywhere in the world—before their estate owes any federal estate tax. For married couples, this effectively doubles to USD 27.98 million.

This exemption is why the US estate tax is often called a “rich person’s tax.” It affects only a tiny fraction of the wealthiest American estates.

For Non-Resident Aliens: The USD 60,000 Prison

For a non-resident alien, the picture is completely different. The exemption is not USD 13.99 million. It is not USD 1 million. It is a fixed, unadjusted USD 60,000—a figure that has remained unchanged for decades.

Any US situs assets above this threshold face progressive taxation beginning at 18% and climbing to a top rate of 40% for taxable amounts exceeding USD 1 million.

The Math is Brutal:

- NRA with USD 100,000 in US stocks: USD 40,000 exposed to tax

- NRA with USD 500,000 in US stocks: USD 440,000 exposed to tax

- NRA with USD 1,000,000 in US stocks: USD 940,000 exposed to tax (and USD 376,000 in tax at 40% rate)

At a 40% rate on USD 440,000, an NRA inheritor with a USD 500,000 portfolio faces a USD 176,000 tax bill—a devastating loss that the Swiss bank will not release until the tax is paid.

Understanding Your Status: Domicile, Not Residency

A critical point of confusion: the US tax code uses different tests for income tax versus estate tax.

For income tax: Objective criteria determine US residency (the “substantial presence test” or “green card test”).

For estate and gift tax: The determining factor is not residency but domicile—a subjective concept based on your intent. The IRS defines domicile as living in a place with “no definite present intention of moving therefrom.”

The distinction is crucial. You can be a US resident for income tax purposes but a non-domiciliary for estate tax purposes, or vice versa. A Swiss resident who spent only a few weeks per year in the US would be classified as a non-domiciliary for estate tax purposes, triggering the USD 60,000 exemption—not the USD 13.99 million exemption.

The Situs Rule: Why Your Swiss Bank Account Offers Zero Protection

International investors frequently believe that holding US investments in a Swiss bank insulates them from US estate tax. This belief is dangerously incorrect.

The location of your brokerage account is irrelevant. What matters is the legal and economic location of the underlying asset itself.

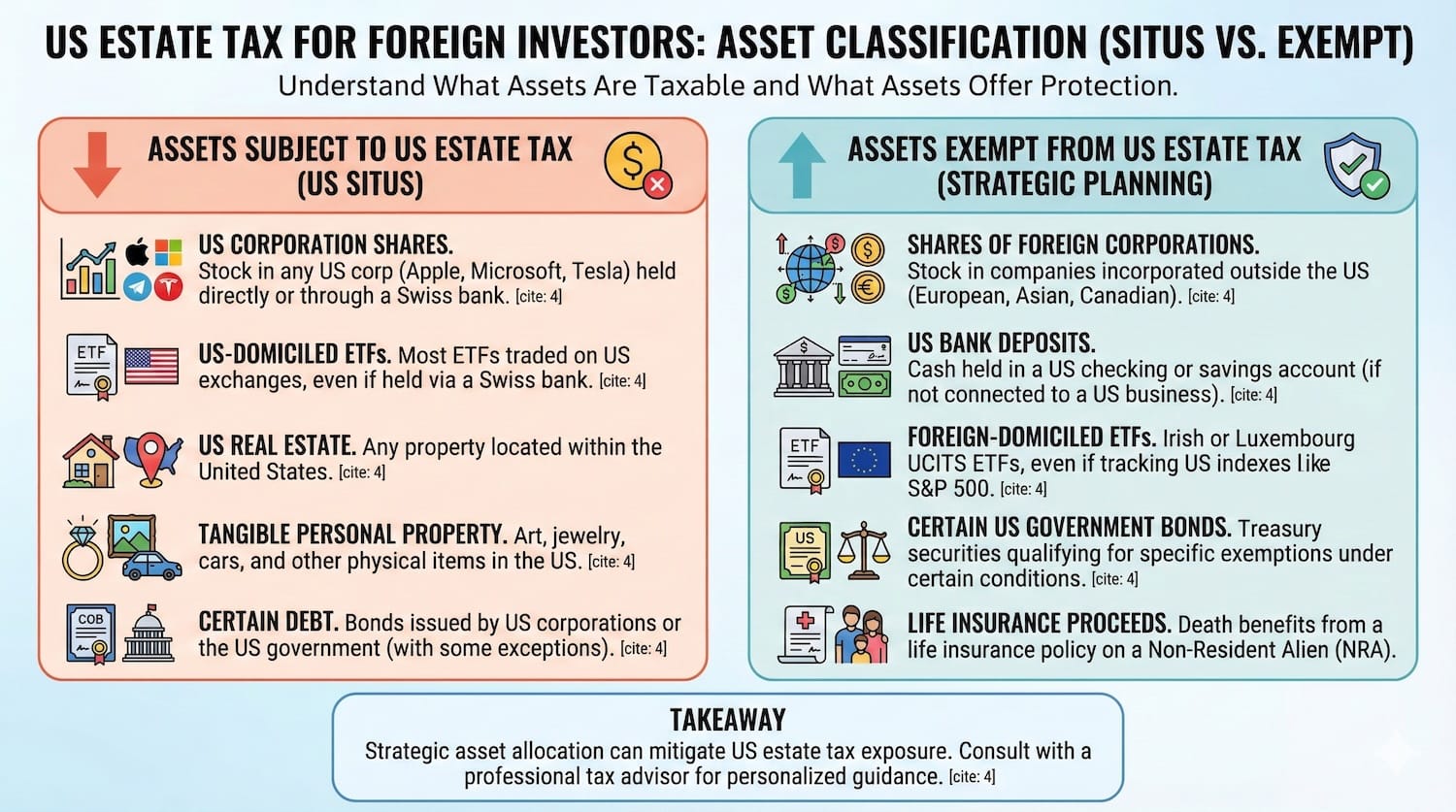

Assets Subject to the US Estate Tax

US Corporation Shares: Stock in Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Tesla—any US corporation. It does not matter whether you hold the shares physically, in a brokerage account, or through a Swiss bank. They are classified as “US situs” assets.

US-Domiciled ETFs: Most ETFs traded on US exchanges are US situs assets, even if you hold them through a Swiss bank.

US Real Estate: Any property located within the United States.

Tangible Personal Property: Art, jewelry, cars, and other physical items located in the US.

Certain Debt: Bonds issued by US corporations or the US government may qualify as US situs (though some debt instruments have specific exemptions).

Assets Exempt From the US Estate Tax

This is where strategic planning begins. Several categories of assets escape the trap entirely:

Shares of Foreign Corporations: Stock in companies incorporated outside the US, including European companies, Asian companies, and Canadian companies. This is a critical planning tool.

US Bank Deposits: Cash held in a US checking or savings account is specifically exempt from US estate tax (as long as the funds are not “effectively connected with a US trade or business”).

Foreign-Domiciled ETFs: An Irish or Luxembourg UCITS ETF is not a US situs asset, even if it tracks the S&P 500. More on this below.

Certain US Government Bonds: Treasury securities qualify for specific exemptions if they meet certain conditions.

Life Insurance Proceeds: The death benefit from a life insurance policy on an NRA is not subject to US estate tax.

The Modern Solution: Irish and Luxembourg UCITS ETFs

Here is a concrete, actionable strategy that most foreign investors are unaware of: You can gain full exposure to US markets without triggering US estate tax by using non-US domiciled ETFs.

How This Works

Instead of holding US-domiciled ETFs (like SPY or VOO), which are US situs assets, you can hold Irish or Luxembourg UCITS ETFs that track the same indices. Examples include:

- iShares Core S&P 500 UCITS ETF (domiciled in Ireland, trading on European exchanges)

- Vanguard S&P 500 UCITS ETF (domiciled in Ireland)

- Amundi S&P 500 UCITS ETF (domiciled in Luxembourg)

Because these ETFs are incorporated in Ireland or Luxembourg—not the United States—the shares are classified as non-US situs assets. Upon your death, the ETF shares are not subject to US estate tax, even though you hold full exposure to the S&P 500.

The Practical Implementation

You instruct your Swiss bank to replace your US-domiciled ETFs (SPY, VOO) with their Irish or Luxembourg UCITS equivalents. This typically involves:

- Selling your existing US-domiciled ETF holdings

- Purchasing the UCITS equivalent

- No tax consequences (within a non-retirement account)

- Identical performance (both track the same index)

- Complete estate tax protection for your heirs

The Cost: Minimal. The transaction costs are the same as any normal ETF trade. The UCITS ETFs trade on European exchanges with tight bid-ask spreads. There is no premium for this estate tax protection.

The Catch: Not all Swiss banks offer UCITS ETFs. You may need to request this specifically or work with a Swiss bank that actively supports European ETF trading. Easy Global Banking can guide this process.

Why This Strategy Is Underutilized

Most financial advisers in Switzerland are unaware of this strategy because they focus on tax-efficient structures for income tax, not estate tax. Additionally, many US-based financial advisers have never heard of UCITS and do not recommend non-US domiciled vehicles.

However, for non-resident aliens, this is one of the most powerful and simple estate tax mitigation tools available.

The US-Swiss Treaty: The “Pro-Rata” Magic

If you are a Swiss domiciliary with US investments, a powerful treaty benefit exists that can reduce your exposure dramatically.

The United States and Switzerland signed an estate and gift tax treaty in 1951. The critical provision allows a Swiss domiciliary to claim a pro-rata share of the much larger US citizen exemption, based on the ratio of US assets to worldwide assets.

The Pro-Rata Formula

Instead of the fixed USD 60,000 exemption, the treaty allows:

(US Situs Assets / Worldwide Estate) × US Exemption Amount = Treaty-Based Exemption

A Real-World Example

Assume you are a Swiss domiciliary with:

- USD 500,000 in US stocks

- USD 4,500,000 in other worldwide assets

- Total worldwide estate: USD 5,000,000

Calculation:

(USD 500,000 / USD 5,000,000) × USD 13,990,000 = USD 1,399,000

Your treaty-based exemption is USD 1,399,000. Since this far exceeds your USD 500,000 US assets, your taxable estate is zero. Your heirs owe zero US estate tax.

Compare this to a Turkish domiciliary with the identical portfolio: USD 440,000 in taxable estate, with a potential tax bill of USD 176,000 at the 40% rate.

The difference between countries: USD 176,000.

This illustrates why domicile is everything.

The Treaty Landscape in 2026

Only approximately 15 countries have estate and gift tax treaties with the United States. They include:

- Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Japan, Netherlands, South Africa, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom

If your country of domicile is not on this list (Turkey, Spain, Mexico, India, Singapore, most Gulf states, most Asian countries), you receive zero treaty benefit. You are stuck with the USD 60,000 exemption.

Strategic Implication: If you are a non-treaty-country domiciliary, the strategies below (lifetime gifts, UCITS ETFs, blocker corporations) are not optional—they are essential.

Strategy 1: The Tax-Free Lifetime Gift

The most straightforward and powerful strategy takes advantage of a remarkable asymmetry in the US tax code.

The Asymmetry Explained

The US imposes estate tax on NRAs for US situs assets at death. However, it explicitly exempts lifetime gifts of those same assets from US gift tax.

Specifically, NRAs are subject to US gift tax only on transfers of US-situs real and tangible property (real estate, art, jewelry). Gifts of intangible property—stocks, bonds, and mutual funds—are completely exempt.

How to Use This

If you hold USD 500,000 in US stocks and wish to pass them to your heirs, you can simply gift the shares during your lifetime. The transaction triggers zero US gift tax. Upon your death, you no longer own these assets, so your estate owes zero US estate tax.

Practical Implementation

- Contact your Swiss bank and request the ability to gift US securities

- Execute a transfer of the shares to your heirs (in your home country, your heir’s home country, or via a trust structure)

- File Form 709 with the IRS (the US gift tax return), which simply reports the gift but claims the exemption

- Repeat annually if desired (there is no limit on the number of gifts you can make, only on the amount that triggers gift tax, which for NRAs is zero for intangible property)

The Catch: Psychological and Practical

The main limitation is psychological. You must relinquish control of the assets during your lifetime. You cannot change your mind or undo the gift. For many investors, this loss of control is unacceptable.

Additionally, the heirs must be identified in advance, and the gift must be made in their names.

Best for: Investors who are comfortable gifting assets to identified heirs, who have clear succession intentions, and who want the simplest solution.

Strategy 2: The Foreign “Blocker” Corporation

For investors who require control, a more sophisticated approach is a foreign corporation that owns the US securities.

How It Works

- Establish a non-US corporation (typically in Ireland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, or the Cayman Islands)

- Transfer your US stocks to the corporation in exchange for shares of the corporation

- You now own shares in a foreign company, not US stocks

- Upon your death, your heirs inherit shares of the foreign corporation

- Since shares of a non-US company are not US situs assets, zero US estate tax is owed

Advantages

- Complete estate tax avoidance: The strategy works regardless of the value of your portfolio

- Retained control: You maintain control of the corporation and its assets during your lifetime

- Flexibility: You can change investment strategy without triggering US estate tax

- Transferable: The shares can be held in a trust, gifted, or transferred as part of estate planning

Disadvantages and Costs

- Setup cost: USD 3,000–8,000 to establish the foreign corporation

- Annual costs: Approximately USD 1,000–2,000 per year for maintenance and compliance

- Income tax complexity: If the heirs are or become US persons, the structure can trigger complex US income tax rules (PFIC—Passive Foreign Investment Company—rules)

- Not for future US persons: If your heirs plan to move to the US or become US citizens, this strategy requires careful modification

Which Country for the Corporation?

Ireland: Popular choice due to tax treaty benefits and EU residency. However, Irish corporations are increasingly scrutinized by the IRS.

Netherlands: Good option with treaty benefits and established international legal framework.

Luxembourg: EU-friendly with strong tax treaty position.

Cayman Islands/BVI: Common for non-treaty countries, but the IRS has more scrutiny of these structures.

The choice depends on your heirs’ anticipated residency and your overall tax situation.

Important Caveat: Substance Requirement

The IRS will not allow a “shell” blocker corporation without substance. The corporation must:

- Have a real business purpose (holding investments qualifies)

- Maintain actual bank accounts and business operations

- File annual corporate tax returns

Anything less risks the IRS disregarding the structure and imposing the estate tax anyway.

Strategy 3: The Foreign Irrevocable Trust

For high-net-worth individuals with complex situations, a properly structured foreign irrevocable trust offers maximum flexibility.

How It Works

- You establish a trust under the laws of a foreign jurisdiction (typically Ireland, the UK, or Jersey)

- You transfer your US stocks to the trust

- The trust holds the assets for the benefit of your designated heirs

- Upon your death, the heirs receive the trust’s benefits without triggering US estate tax

Advantages

- Maximum flexibility: The trust can be amended to accommodate changing circumstances

- Professional management: A professional trustee can manage the assets and investments

- Generational planning: Trusts can be structured to benefit multiple generations

- Asset protection: Trusts provide liability protection from creditors

Disadvantages

- High setup cost: USD 15,000–30,000+ to establish a properly drafted international trust

- Ongoing administration: Annual trustee fees, tax filings, and accounting

- Complexity: Requires qualified international tax and legal counsel

- Irrevocable nature: Once established, you cannot unwind the trust

- Control loss: You must relinquish control to the trustee

Best for: Ultra-high-net-worth individuals with USD 5 million+ in US assets, complex family situations, and multi-generational planning objectives.

What Happens if You Do Nothing: The Catch-22

For those who fail to plan, the consequences are severe and well-documented.

The Timeline of Disaster

Day 1 (Death): The Swiss bank freezes your US securities account upon notification of death.

Day 9 (Month 1): Your heirs contact the bank requesting access. They are informed that the assets remain frozen pending IRS clearance.

Month 3: The estate executor files Form 706-NA (US Estate Tax Return for Non-Residents) with the IRS. This requires disclosure of your entire worldwide estate, regardless of whether those assets are subject to US tax.

Month 9: The estate tax payment is due. The executor must pay approximately 24–40% of the US situs assets in tax. However, the frozen account prevents access to funds.

The Liquidity Trap: The family must find liquidity from other sources (selling non-US assets, borrowing, liquidating the foreign estate) to pay a US tax bill on assets they cannot access.

Month 12–18+: The IRS processes the Form 706-NA and issues (or delays issuing) the Federal Transfer Certificate. Only with this certificate will the Swiss bank release the frozen assets.

Final Result: Assets that should have been inherited smoothly are now subject to a 40% haircut, the family has endured 18+ months of frozen assets and bureaucratic frustration, and they have incurred thousands of dollars in legal and accounting fees.

The 2026 Roadmap: Action Steps by Domicile Status

If You Are a Swiss Domiciliary with US Stocks

Priority 1: Verify Treaty Eligibility

Consult a qualified international tax adviser to confirm your eligibility for the US-Swiss treaty pro-rata exemption. Calculate your treaty-based exemption using the formula above.

Priority 2: If You Exceed the Treaty Exemption

If your US stocks exceed your treaty-based exemption, implement one of the three strategies above. For simplicity: switch to Irish/Luxembourg UCITS ETFs. For control: establish a foreign blocker corporation.

Priority 3: Document Your Planning

File Form 709 (if you make lifetime gifts) or establish formal documentation of your corporate or trust structures. The IRS will scrutinize these arrangements.

If You Are a Non-Treaty-Country Domiciliary (Turkey, Spain, Mexico, India, Singapore, etc.)

Priority 1: Act Immediately

The USD 60,000 exemption is fixed, and there is no treaty relief. Any US situs assets above this threshold are exposed to a 40% tax.

Priority 2: Switch to UCITS ETFs

This is the simplest, lowest-cost solution. Replace any US-domiciled ETFs with Irish or Luxembourg UCITS equivalents. Cost: minimal (one transaction). Benefit: complete estate tax elimination.

Priority 3: Consider a Blocker Corporation

If you hold individual US stocks or expect significant future gains, establish a foreign blocker corporation. The one-time setup cost (USD 5,000–8,000) and annual costs (USD 1,000–2,000) are easily justified by the estate tax savings.

Priority 4: Gift Assets if Comfortable

If you are comfortable relinquishing control, annual lifetime gifts to designated heirs are tax-free and reduce your taxable estate.

If You Are Planning to Move to Switzerland or Another Treaty Country

Before Moving: If you currently hold US stocks, consider establishing a blocker corporation while you are still a non-treaty domiciliary. Once you move and establish Swiss domicile, moving the assets into the trust-like structure becomes more complex.

Cost and Timeline Comparison

| Strategy | Setup Cost | Annual Cost | Timeline | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switch to UCITS ETFs | $0 (trade cost only) | $0 | 2–4 weeks | 100% (complete elimination) |

| Lifetime Gifts | $0 | $500–1,000 (Form 709 filing) | 2–6 weeks | 100% (tax-free) |

| Foreign Blocker Corp | $5,000–8,000 | $1,500–2,500 | 4–8 weeks | 100% (complete elimination) |

| Foreign Irrevocable Trust | $15,000–30,000+ | $3,000–5,000+ | 8–12 weeks | 100% (complete elimination) |

Why 2026 Compliance Pressure Is Intensifying

As we enter 2026, three specific factors make immediate action critical:

1. TCJA Sunset Revenue Pressure

The federal government will face revenue pressure from the halving of the US citizen exemption. This creates incentives to increase collection from foreign estates.

2. IRS Modernization Initiatives

The IRS is investing in new compliance systems and international coordination. The days of structures being overlooked are ending.

3. CRS Reporting Expansion

The Common Reporting Standard (CRS) now requires automatic reporting of foreign financial accounts to tax authorities. The IRS has access to unprecedented visibility into foreign-held US assets.

Bottom line: The IRS in 2026 is more capable and more motivated than ever to enforce the USD 60,000 exemption against unprepared estates.

Strong Disclaimer

This article provides general information about US estate tax and is not legal or tax advice. The US estate tax system is extraordinarily complex. US tax laws change frequently and are subject to reinterpretation by the IRS and courts.

Your specific situation may involve factors not covered in this guide, including:

- Your country of domicile and treaty eligibility

- The nature and value of your worldwide assets

- The citizenship and residency of your heirs

- Your anticipated future residency changes

- State-level estate taxes (some US states impose their own estate taxes)

You must consult with a qualified international tax lawyer and accountant before implementing any strategy. The cost of this consultation (typically USD 2,000–5,000) is trivial compared to the potential tax savings and the cost of correcting errors after death.

Do not rely on general advice from your Swiss bank advisor (who may lack US estate tax expertise). Do not rely on US-based accountants unfamiliar with non-resident alien rules. Engage counsel with specific experience in international estate planning for foreign investors.

Conclusion: From Trap to Tactical Advantage

The US estate tax system is designed to surprise and devastate unprepared foreign investors. A USD 500,000 portfolio becomes a USD 120,000 problem. A USD 1 million portfolio becomes a USD 376,000 problem.

But this outcome is entirely avoidable.

For Swiss domiciliaries, the treaty pro-rata benefit may provide complete exemption, requiring no action. Verify this with a qualified adviser.

For non-treaty-country domiciliaries, the path is clear:

- Simplest solution: Switch to Irish/Luxembourg UCITS ETFs (cost: negligible, timeline: 2 weeks)

- More control: Establish a foreign blocker corporation (cost: USD 5,000–8,000 upfront + annual maintenance, timeline: 4–8 weeks)

- Maximum flexibility: Establish a foreign irrevocable trust (cost: USD 15,000–30,000+ upfront + ongoing administration, timeline: 8–12 weeks)

The difference between action and inaction is not measured in thousands of dollars—it is measured in hundreds of thousands of dollars, plus years of bureaucratic frustration for your heirs.

For any foreign national with US investments, engaging qualified international tax and legal counsel is not a luxury. It is an absolute necessity. The cost is trivial compared to the benefit. And in 2026, with increased IRS scrutiny and the TCJA sunset creating new compliance pressures, the time to act is now.