Switzerland’s cross-border banking model—quietly built over decades on national exemptions, relationship-driven servicing, and regulatory pragmatism—is about to hit a structural wall. From 11 January 2027, the European Union’s revised Capital Requirements Directive VI (CRD VI) eliminates most flexibility that Swiss banks have used to serve EU clients without establishing costly, supervised presences in individual Member States. The change is not incremental. It rewrites the economic logic of cross-border wealth management and corporate banking between Switzerland and the EU, forcing Swiss institutions to choose between expensive onshoring, strategic retreat, or radical restructuring of client relationships.

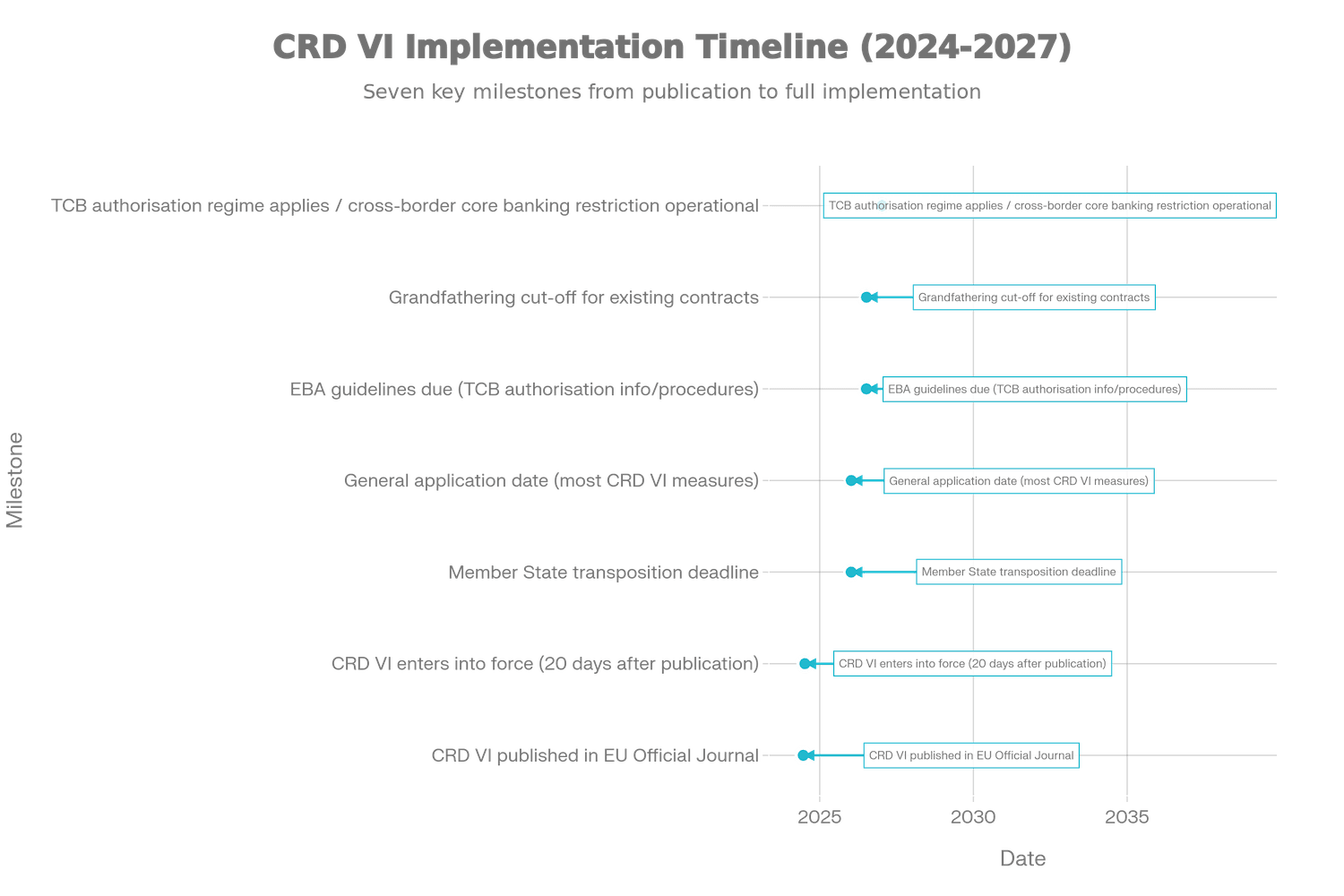

For Swiss private banks, corporate lenders, and neo-banks with EU client exposure, the window to decide—and execute—is already closing. Member States must transpose CRD VI into national law by 10 January 2026, and most provisions take effect immediately. The third-country branch regime, which governs how Swiss banks may continue serving EU clients, applies from 11 January 2027. That leaves 12 to 18 months to secure authorisations, build governance infrastructure, migrate client relationships, and train front-office staff to operate within far tighter perimeter controls.

Why CRD VI hits Switzerland harder than other jurisdictions

Switzerland manages approximately CHF 1 trillion in assets for EU-domiciled private clients—roughly 40% of all cross-border private wealth managed from Switzerland. This business employs around 20,000 people in Switzerland and generates CHF 1.5 billion annually in taxes and levies. Swiss banks hold a 25% global market share in cross-border wealth management, making the sector a true export industry.

The EU market matters not only because of its scale but because of its structure. Unlike the United States or Singapore, where Switzerland has negotiated mutual recognition frameworks (such as the Berne Financial Services Agreement with the UK, effective 1 January 2026), the EU has moved in the opposite direction—toward establishment requirements, supervisory harmonisation, and elimination of light-touch national exemptions.

CRD VI does not simply raise compliance costs. It forces Swiss banks to decide whether they are willing to operate as supervised EU entities in each country where they conduct core banking activities—or exit those markets entirely.

CRD VI implementation timeline (what happens when)

What changes on 11 January 2027: the Article 21c regime

CRD VI’s Article 21c introduces a harmonised, EU-wide rule: third-country undertakings (including Swiss banks) that provide core banking services to clients or counterparties established or situated in an EU Member State must do so through an authorised third-country branch in that Member State—or qualify for one of a handful of narrow exemptions.

“Core banking services” are defined by reference to Annex I, points 1, 2, and 6 of the Capital Requirements Directive, which cover:

- Deposit-taking and other repayable funds

- Lending (including consumer credit, mortgages, factoring, and trade finance)

- Guarantees and commitments

The effect is stark: activities that Swiss banks have historically conducted from Switzerland via cross-border servicing models now require EU establishment unless the bank can credibly argue that an exemption applies.

Critically, third-country branches cannot passport across the EU. A Swiss bank that establishes a branch in Germany cannot use that branch to serve clients in France, Italy, or the Netherlands. Each Member State requires separate authorisation, separate governance, and separate supervisory reporting. This is a fundamental departure from the intra-EU passporting regime that benefits EU credit institutions, and it makes multi-country EU strategies structurally more expensive for Swiss banks.

The exemptions: narrow, evidence-heavy, and defensible only with discipline

Article 21c includes several exemptions, but each is tightly constructed and subject to supervisory scrutiny.

Reverse solicitation (client-initiated service provision)

Where a service is provided at the exclusive initiative of the EU client or counterparty, the Swiss bank is not required to establish a branch. The EBA’s July 2025 report makes clear that “exclusive initiative” means exactly that: any form of solicitation—whether by the bank itself, an affiliate, an intermediary, or even through general brand advertising targeted at EU audiences—negates the exemption.

The EBA has also clarified that:

- Marketing activities (including digital targeting, sponsorships, and influencer arrangements) are incompatible with reverse solicitation.

- The exemption is limited to the specific categories of products or services initially solicited by the client, though it extends to services “necessary for, or closely related to” the original request.

- Broadening the relationship into unrelated products or services requires fresh evidence of client initiative—or risks triggering the establishment requirement.

In practice, this means Swiss banks relying on reverse solicitation must implement forensic-grade documentation:

- Timestamped, auditable records of inbound client requests

- Controls to prevent relationship managers from proactively proposing new core banking products

- Marketing and digital acquisition strategies that demonstrably avoid EU-targeted solicitation

- Ongoing compliance monitoring to ensure staff behaviour does not “taint” the exemption through travel, events, or informal outreach

Reverse solicitation is not a scalable growth strategy. It is a defensive posture for maintaining existing relationships under strict evidentiary discipline.

Interbank and intragroup exemptions

Core banking services provided to other credit institutions (interbank) or within the same group (intragroup) are exempt from the branch requirement. These carve-outs are operationally useful but do not solve the problem for Swiss private banks or corporate lending franchises serving retail or commercial counterparties in the EU.

MiFID-related carve-out

Where core banking services are provided as ancillary services to investment services governed by MiFID II, and where those investment services are the primary activity, banks may benefit from an exemption. This is particularly relevant for wealth management models where custody, cash management, or Lombard lending support a broader investment advisory relationship. However, the boundary is fact-specific, and any shift toward core banking as a primary activity risks pulling the entire relationship back into CRD VI scope.

Grandfathering (contracts signed before 11 July 2026)

Contracts for core banking services signed before 11 July 2026 may continue to be serviced without a branch until 11 January 2027. But amendments, refinancings, rollovers, or changes to counterparties may void this protection. Swiss banks should treat any material change to a grandfathered contract as potentially “new business” subject to the full Article 21c regime.

Germany: the end of BaFin exemption letters

Germany has been a critical market for Swiss banks, in part because the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin) historically granted individual exemptions under Section 2(5) of the German Banking Act (KWG) to major Swiss, US, and Canadian banks conducting cross-border business without a branch.

CRD VI eliminates this flexibility. Germany’s draft CRD VI Implementation Act (BRUBEG), published in August 2025, requires BaFin to revoke existing exemptions to the extent they conflict with Article 21c. The draft law does not entirely abolish Section 2(5) exemptions, but it subordinates them to CRD VI’s branch requirement for core banking services.

The German Ministry of Finance has implicitly confirmed that reverse solicitation will continue as an exemption under the new regime, consistent with longstanding BaFin practice. However, the burden of proof now sits squarely with the bank, and the margin for interpretive flexibility has narrowed significantly.

For Swiss banks that have built German client franchises on the assumption that BaFin letters would remain available, the message is unambiguous: establish a branch, restructure the offering, or exit.

Strategic options: what Swiss banks can actually do

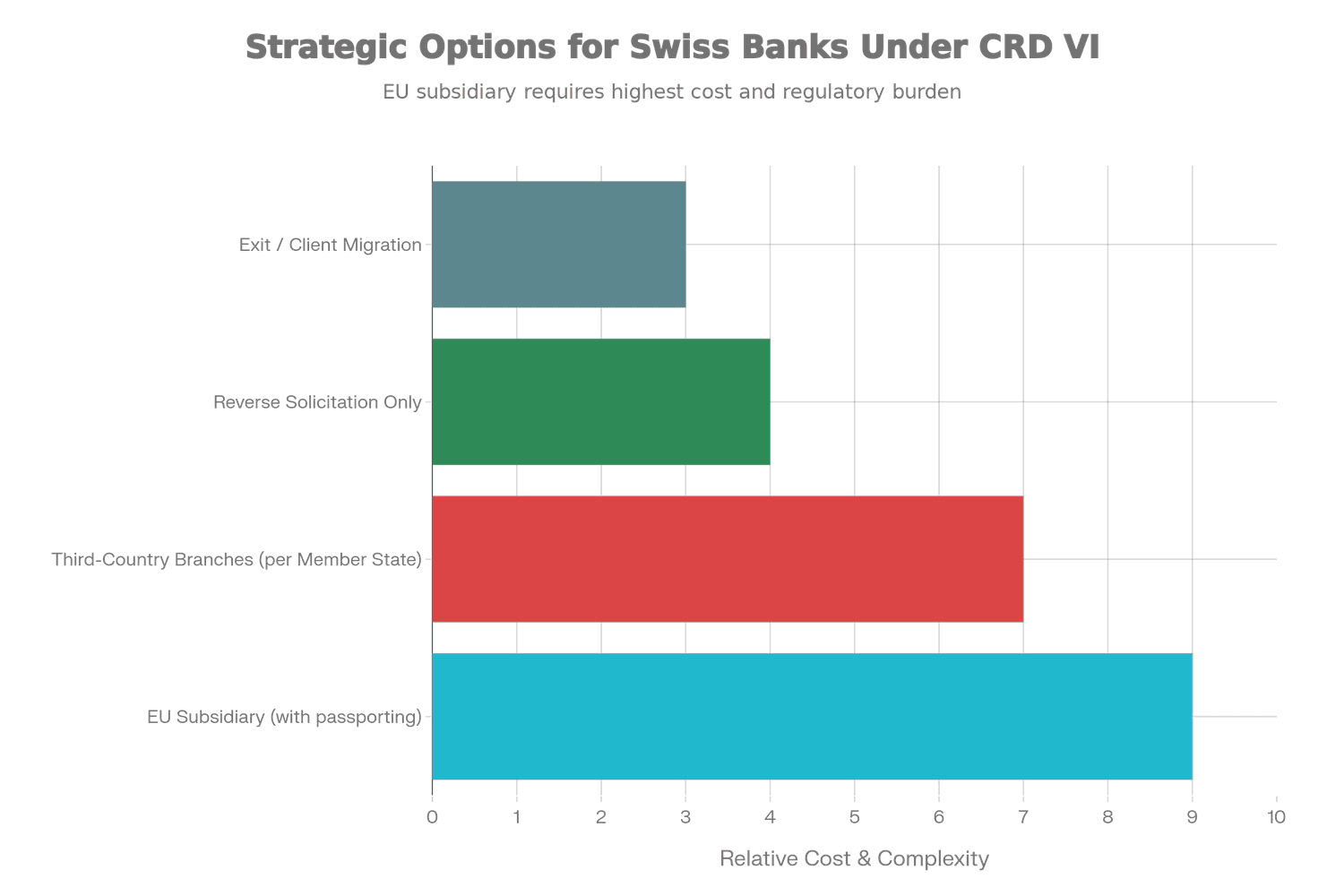

Swiss banks face four principal pathways under CRD VI. Each involves trade-offs between cost, scalability, regulatory burden, and strategic flexibility.

Strategic options for Swiss banks: cost and complexity comparison

1. Establish an EU subsidiary (credit institution)

An EU subsidiary—typically structured as a credit institution licensed in a single Member State—can passport its services across the EU under the Single Market framework. This is the only structure that provides true pan-European scalability without requiring multiple national authorisations.

Advantages:

- Full EU market access via passporting

- Ability to consolidate EU operations under a single legal entity

- Potential to relocate high-value client relationships into a regulated, supervised EU environment

Disadvantages:

- Highest setup and ongoing cost (capital requirements, governance, compliance infrastructure)

- Requires significant operational restructuring (booking models, IT systems, legal entities)

- Ongoing prudential supervision by an EU regulator, not just FINMA

When it works: Multi-country EU client exposure, strategic commitment to EU growth, sufficient scale to justify the investment.

2. Establish third-country branches in select Member States

A third-country branch is a lighter alternative to a subsidiary but comes with critical limitations: no passporting across Member States. A branch established in France cannot serve clients in Germany; a branch in Italy cannot serve clients in Spain.

Advantages:

- Lower capital and regulatory burden than a subsidiary

- Localised compliance footprint (only the host Member State’s rules apply to the branch’s activities in that state)

Disadvantages:

- Requires multiple branches for multi-country coverage

- No economies of scale across Member States

- Increasingly stringent governance, liquidity, and reporting standards under CRD VI

When it works: Concentrated exposure in one or two high-value EU countries (e.g., Germany and France), where the cost of branch authorisation is justified by client revenue.

3. Rely exclusively on reverse solicitation

For banks with low growth ambitions in the EU, or where the client base is already well-established and stable, reverse solicitation may be a viable path. This approach avoids the cost of EU establishment but demands rigorous controls and continuous documentation.

Advantages:

- No licensing or establishment costs

- Maintains Switzerland as the booking centre

- Suitable for existing client relationships with low turnover

Disadvantages:

- Not scalable for client acquisition or product expansion

- High evidentiary burden and compliance risk

- Marketing, digital acquisition, and proactive relationship management are effectively prohibited

When it works: Defensive posture for maintaining legacy relationships; wealth management models where clients are genuinely initiating contact.

4. Exit or migrate clients

For low-margin, high-risk corridors, the most rational response may be strategic exit—either by ceasing to serve EU clients in those segments or by migrating clients to an EU partner bank or an existing EU subsidiary.

Advantages:

- Eliminates legal and reputational tail risk

- Simplifies compliance perimeter

- Avoids sunk costs in markets where returns do not justify the regulatory investment

Disadvantages:

- Revenue loss and client attrition

- Reputational handling required (especially for long-standing client relationships)

When it works: Marginal EU exposures, commoditised products, or segments where CRD VI compliance costs exceed expected profitability.

The Switzerland-UK contrast: what mutual recognition looks like

On 1 January 2026, the Berne Financial Services Agreement (BFSA) between Switzerland and the United Kingdom entered into force. The BFSA creates a mutual recognition framework for cross-border financial services, allowing UK and Swiss firms to serve wholesale and sophisticated clients in each other’s jurisdictions by deferring to the regulatory and supervisory rules of the home country.

The BFSA is explicitly designed to avoid the need for firms to navigate unfamiliar rules or establish costly local subsidiaries. It covers asset management, banking, insurance, and investment services, and is based on the principle that the UK and Swiss regulatory regimes achieve equivalent outcomes in market integrity, financial stability, and client protection.

The contrast with the EU’s CRD VI approach could not be sharper. Where the BFSA enables cross-border access based on home-country supervision, CRD VI mandates establishment and host-country supervision for core banking services. The BFSA is a model of regulatory cooperation; CRD VI is a perimeter-hardening exercise that assumes third-country supervision is insufficient unless paired with EU establishment.

For Swiss banks, the BFSA offers a glimpse of what market access could look like under a different regulatory philosophy—and underscores the structural cost that CRD VI imposes.

What Swiss banks must do now: the seven-step CRD VI playbook

The timeline is unforgiving. Member States transpose CRD VI by 10 January 2026; the third-country branch regime applies from 11 January 2027. Swiss banks need 12 to 24 months to secure authorisations, build governance infrastructure, and migrate clients. That means decisions must be made now.

1. Build an Article 21c inventory

Create a matrix of all EU client relationships, mapping:

- Service type (lending, deposits, guarantees, investment services)

- Client domicile (by Member State)

- Booking location (Switzerland vs. EU entity)

- Relationship manager location and travel patterns

- Communication channels (digital, phone, in-person)

- Marketing source (inbound, targeted campaigns, intermediaries)

The objective is to identify exposure to Article 21c’s scope and quantify the revenue and client counts at risk.

2. Re-segment clients by regulatory deliverability

Do not segment only by wealth or profitability. Segment by regulatory feasibility:

- EU residents needing core banking services → likely require onshore presence from 2027

- EU residents primarily using investment services → may remain offshore with careful boundary management

- Clients with demonstrable reverse solicitation evidence → defensible for continuation under strict controls

3. Decide the footprint: subsidiary, branches, or hybrid

If the bank has multi-country EU exposure, a subsidiary hub is often the only scalable solution—despite higher cost—because branches do not passport. If exposure is concentrated in one or two countries, a single third-country branch per country may be viable, accepting that growth into other EU states will require additional establishments.

4. Harden reverse solicitation controls

Reverse solicitation is explicitly preserved as an exemption, but only under strict conditions. Controls must include:

- Inbound trigger documentation (timestamp, channel, client statement)

- Pre-approval workflows for any proposal of new products

- Marketing reviews to ensure no EU-targeted campaigns

- Staff training on the difference between “responding to client requests” and “proactive selling”

- Audit trails for supervisory review

Treat reverse solicitation as an evidentiary standard, not a legal theory.

5. Re-engineer front-office behaviour

Most perimeter failures come from:

- Relationship managers travelling to EU countries and conducting business meetings

- “Service continuation” drifting into new product proposals

- Informal advice given during conferences, events, or dinners

CRD VI makes these behaviours legally expensive. Banks must implement pre-travel approvals, client interaction protocols, and escalation paths for any activity that could be interpreted as solicitation.

6. Stress-test grandfathering assumptions

CRD VI includes transition provisions, including the ability to service contracts signed before 11 July 2026 without a branch until 11 January 2027. But amendments, refinancings, rollovers, and changes to counterparties may void the protection.

Treat any material change as potentially “new business” and re-assess the establishment requirement.

7. Align with FINMA’s cross-border risk expectations

FINMA has long signalled that cross-border legal and reputational risk must be actively managed, and that banks must define target-market service models consistent with foreign law. That matters now because CRD VI makes EU-side enforcement easier to trigger and easier to evidence.

Elevate EU cross-border perimeter risk into the bank’s operational risk framework, with key risk indicators (KRIs), escalation paths, and board-level governance.

If Swiss banks are looking for practical guidance on opening compliant accounts and navigating cross-border regulatory frameworks, a direct path is here:

Open Swiss Bank Account → https://www.easyglobalbanking.com/open-swiss-bank-account/

What CRD VI means for Switzerland’s competitive position

CRD VI is not just a compliance project. It is a market access shock that compresses the economic viability of Switzerland’s cross-border banking export model. The EU represents 40% of Switzerland’s cross-border private wealth and CHF 1 trillion in assets. If Swiss banks cannot serve those clients profitably under the new regime, the revenue, employment, and tax base tied to that business will migrate—either to EU-domiciled competitors or to offshore centres with better EU market access agreements.

The Berne Financial Services Agreement with the UK demonstrates that mutual recognition frameworks are possible, but the EU has chosen a different path: onshoring, supervision, and establishment requirements. Switzerland’s openness to foreign banks does not guarantee reciprocal treatment from the EU.

For Swiss banks, the strategic question is no longer whether CRD VI will change the business—it will. The question is how much of the EU business is worth defending, and at what cost.

The cost of waiting

CRD VI is scheduled. The deadlines are fixed. The EBA is building implementation guidance, Member States are transposing, and supervisors are preparing to enforce. Swiss banks that wait until mid-2026 to decide will face rushed restructurings, client friction, licensing delays, and enforcement risk.

The institutions that will navigate CRD VI successfully are the ones acting now:

- Quantifying exposure

- Choosing a defensible footprint

- Rebuilding perimeter controls

- Training staff

- Migrating clients with a plan that looks credible to both EU supervisors and FINMA

For readers exploring cross-border banking options—whether in Switzerland, Singapore, or other jurisdictions—Easy Global Banking provides end-to-end support for compliant account opening and market access strategies across regulatory perimeters.